Insights on Value Capture and Growth Readiness

How industrial owners build resilience, attract capital, and capture the next layer of value before they sell.

The Capital Window Is Closing: Why “Good Companies” Are Suddenly Stranded

Capital hasn’t vanished—it’s just become selective. After years of easy money, banks and private credit have shifted from rewarding growth to rewarding resilience. Owners who can show clear systems, disciplined decision-making, and measurable results will still raise, refinance, and grow. The next era belongs to companies that stay bankable, buyable, and buildable when the window narrows.

“Every credit index, we’re tightening across the board.” — Don McCree, Head of Commercial Banking, Citizens Financial Group, Q3 2025 Earnings Call

Across the lower middle market, capital hasn’t disappeared; it’s simply become selective. The Fed’s Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey shows that nearly half of U.S. banks tightened commercial lending standards for mid-sized borrowers through late 2024 and early 2025. GF Data reports deal volume down more than 30 percent from its 2021 peak. Private credit, despite managing more than $1.6 trillion globally, has narrowed its focus to sponsor-backed or governance-mature borrowers.

Capital still flows, but only to those who treat resilience as an operating system. In this cycle, allocators—not operators—define who stays bankable, buyable, and buildable.

Market Evidence: The Window Narrows

The tightening began in 2023 when rate policy and regulation started pulling in the same direction. After the collapses of Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic, new Basel III capital rules and tougher oversight pushed regional banks to hold more reserves against commercial loans. By early 2024, many lenders in the $10 to $100 billion asset range had scaled back new credit for owner-led companies.

At the same time, deposit costs surged. The average rate on interest-bearing deposits climbed from 0.06 percent in 2021 to more than 4 percent by mid-2024. That swing erased the margins regional banks once earned on low-cost liquidity. Most responded by stepping away from segments that demanded more monitoring and carried less collateral protection, with the lower middle market among the hardest hit.

Private credit stepped into the gap but cautiously. The sector now manages more than $1.6 trillion globally, up from $875 billion in 2020, according to Preqin. Yet underwriting has become stricter. Funds prefer sponsor-backed deals with strong reporting and governance. Independently owned firms often do not make it past screening.

Deal activity tells the same story. GF Data shows lower-middle-market volume down by roughly a third since 2021. Purchase multiples have fallen from about 7.5× to 6× EBITDA, and leverage has dropped nearly a full turn.

Liquidity hasn’t vanished. It has shifted toward companies that show discipline—those that act like stewards of capital, not just producers of it.

Owner Diagnosis: Why “Good” Companies Are Failing the Test

Many owners blame sentiment, but the change runs deeper. Credit and equity markets have moved from rewarding performance to rewarding resilience.

In 2021, profit was proof enough. With near-zero interest rates and abundant private capital, almost any solid balance sheet could attract financing. When the Federal Funds Rate rose from 0.25 percent to over 5 percent by mid-2023, borrowing costs multiplied and lenders began screening for durability instead of yield.

That is where many mid-market firms have hit a wall. They are efficient but hard to evaluate. Few have formal governance or automated reporting. Many cannot show how decisions get made or how cash is redeployed under pressure. The business works, but to outsiders it looks opaque.

This lack of visibility reads as risk. Lenders tighten covenants or walk away. Investors discount valuations or extend diligence. What owners experience as a liquidity problem is really a transparency problem, a re-pricing of trust.

Capital is still available. It is looking for companies that behave like investors in their own enterprise—the ones that make decisions with evidence, measure risk in real time, and can explain how they create value, not just that they do.

Allocator Solution: How Resilience Becomes Capital

The firms still raising capital or completing acquisitions have one thing in common: visible system maturity. Their lenders can trace how money moves through the business, from operations to reinvestment. They can see the logic, not just the results.

These companies treat resilience as a working asset. They build models that bend under pressure without breaking: recurring revenue, flexible cost structures, and governance that shortens the distance between signal and decision. When outsiders can see that discipline, they price the risk lower.

More owners are starting to operate this way, thinking like allocators rather than operators. The shift is practical, not theoretical. It comes down to three habits:

Measure resilience before you need it. Track liquidity, customer concentration, and reporting reliability as if a lender were already testing them.

Plan in short allocation cycles. Replace rigid annual budgets with ninety-day reviews that tie strategy directly to measurable deployment of time and capital.

Make the story match the structure. Ensure your stated strategy aligns with how the business actually spends and invests.

These are not new ideas. They have simply become the price of admission. The gap between “good company” and “credible borrower” now depends on the quality of evidence. Firms that institutionalize discipline earn cheaper debt, faster diligence, and stronger options when markets reopen.

In today’s market, maturity is not about size. It is about visibility. Operational strength alone is no longer enough. Resilience, made measurable, is what keeps a company bankable, buyable, and buildable.

Call to Action: The Discipline Dividend

Tight cycles separate effort from evidence. When money was cheap, almost any business could look like a safe bet. When the cost of capital rises, lenders and buyers look harder. What they are really searching for is proof that the company’s strength is not a story but a system.

This market is not hostile. It is honest. Owners who can show resilience—clear books, tested decisions, predictable cash—will still raise money and close deals. Those who build discipline into how they plan and invest will find that credibility travels further than optimism.

Now is the time to make your systems visible. Write down how capital gets deployed, how you adjust when pressure hits, how your team measures risk and reward. Build the habits before the next up-cycle so you can use them when it arrives.

The companies that do this will define the next phase. They will stay bankable when credit tightens, buyable when markets reopen, and buildable through every turn that follows.

PE Is Not Buying EBITDA. It’s Buying Confidence.

Private equity doesn’t buy earnings—it buys confidence. When investors look at a company, they’re underwriting its ability to deliver future performance, not just its past EBITDA. This piece explores how “confidence gaps” in systems, leadership, and reporting quietly discount valuation—and what owners can do to close them before they sell.

Markets do not reward history; they discount uncertainty

“We don’t pay for last year’s EBITDA. We pay for the confidence we can grow next year’s.”

The remark, delivered without theatrics by a mid-market private equity partner, is inelegant but accurate. Multiples are not a reward for past excellence; they are a probability-weighted forecast of future execution. In lower mid-market SMB industrial deals, the real negotiation is not over price but over conviction.

This is why the same company can receive wildly different valuations from different buyers. The spread is not sentiment; it is risk discounting. PitchBook estimates that fewer than three percent of owner-led firms successfully complete a traditional sell-side process, while capital concentration continues to narrow toward funds with scale and confidence in post-close lift.

McKinsey’s study Beyond the Hockey Stick finds that roughly ten percent of firms capture more than eighty percent of total economic value creation over a decade. The distribution is not linear; it is a power law, and private capital prices accordingly. The pricing function is therefore a risk-adjusted forecast: is this company one of the ten percent that can compound, or one of the ninety percent that will merely endure? The buyers that are still deploying are selective, not generous.

Underwriting is the sorting mechanism.

Owners think they are being judged; the risk they absorb is being underwritten

The key misunderstanding among owners in industrial SMB manufacturing is that investors are pricing the business as it exists today. They are not. They are pricing how much of today’s EBITDA will still be standing once the owner leaves the room—and how quickly a buyer can compound it thereafter. A clean P&L does not answer that question. A QoE cannot answer it either. Only the operating system of the company can.

The underwriting sequence is blunt. First: “Is this company durable without the current owner?” Second: “Can we institutionalize what works without overpaying for the privilege?” Third: “Is the growth story credible inside the four walls, not just in the offering memorandum?” The multiple is not a judgment of worth but an output of underwriting: the present value of future net cash flows and terminal value. It is then discounted by the capital injections and execution risk required to achieve them.

Growth is not rewarded; legibility is

In one recent diligence discussion, the room stalled on the simplest of questions: “What business are we actually buying?” The owner had healthy EBITDA, a loyal customer base, and sensible unit economics. The problem was strategic drift. Five initiatives were being pursued at once, each potentially attractive, but none coherent. What looked like optionality to the operator appeared as drift to the buyer. The haircut was not punishment. It was uncertainty, priced.

Bain’s research on adjacency moves in industrial firms finds that more than 70 percent of unfocused expansions underperform their core, not because the markets are unattractive but because the operating system was never built to carry that variety.

This is the quiet truth of lower mid-market industrial underwriting: most valuation erosion is not caused by obvious weaknesses but by ambiguous intentions. Buyers can underwrite a bottleneck in a manufacturing or industrial SMB environment. They can underwrite a thin bench. They can even underwrite cyclicality if there is discipline in cash conversion. What they cannot underwrite is a company without a crisp answer to “why this model, at this scale, with this focus.”

Owner-reliance is therefore not the root concern; it is merely the most visible proxy for something larger: concentration of judgment. When all strategic direction lives in one head, the buyer assumes execution risk remains unpriced. The same dynamic applies to firms with sprawling initiative sets, product creep, or half-adjacent expansions justified only by “customers asked for it.” The fear is not mismanagement. The fear is diffusion.

For investors, confidence is not a feeling; it is infrastructure. It shows up in routinized decisions, reliable reporting cadence, constraint-aware capital allocation, and a recognizably bounded strategy. Growth, in that context, is not a hope but a process, and what many owners call exit readiness is simply the point at which the operating system becomes legible to a buyer. The more predictable the process, the narrower the haircut.

This is why the best offers do not reward scale so much as clarity. A smaller firm with a defensible core and visible path to systematized expansion will often outprice a larger firm with a blurred identity. Size without focus is not resilience. It is leverage without a thesis.

The market’s selectivity is frequently misread as stinginess. It is better understood as underwriting discipline. When capital is choosy, ambiguity is expensive. What is being purchased is not the last twelve months of performance but the institutional momentum of the next thirty-six.

In the end, what is being priced is legibility.

A company easy to read is a company easy to scale.

Originally published on LinkedIn. Updated and republished here with additional insights.

The Resilience Hierarchy: A Framework for Enduring Growth

The Resilience Hierarchy outlines five levels of business maturity—from liquidity to legacy—that predict whether growth endures or collapses.

Resilience is not grit; it is the deliberate design of systems that prevent reliance on heroics.

Resilience has become one of the most valuable yet elusive qualities in business. It is often confused with grit. Grit asks individuals to persevere through adversity by sheer willpower. Resilience, in contrast, is about designing systems so that endurance is not left to human stamina alone.

The distinction is visible in polar history. The crew of the Endurance, led by Ernest Shackleton, survived only by extraordinary grit after their ship was crushed by ice. By comparison, Fridtjof Nansen’s Fram was designed with a rounded hull that allowed it to ride above the pack ice rather than be destroyed by it. The crew still faced hardship, but they did not need superhuman endurance simply to survive. The difference was not in courage but in design.

Businesses face the same choice. They can rely on grit—leaders and employees working harder, longer, and under increasing strain—or they can build resilience into the enterprise itself. The Resilience Hierarchy offers a framework for doing the latter.

The model adapts the logic of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to the realities of business growth. But unlike Maslow’s psychology, which aims for self-actualization, the Resilience Hierarchy is built as a constraint system, with future free cash flow as the objective function. Every for-profit enterprise has the same ultimate goal: to increase free cash flow. This delivers money to owners, lowers the cost of capital, and raises enterprise value. The hierarchy exists to help leaders identify and address the constraint most likely to limit those flows.

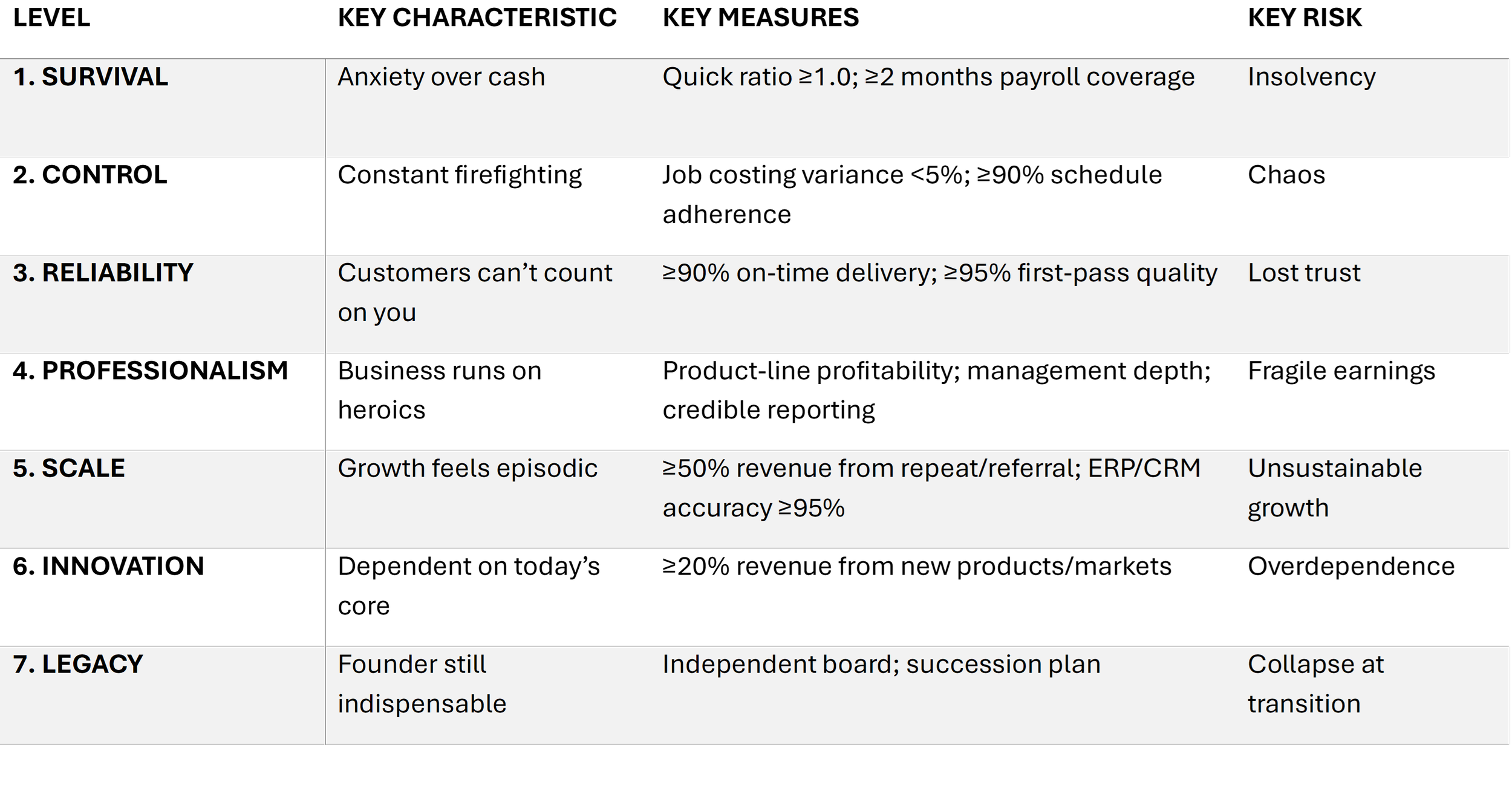

The hierarchy identifies seven levels of resilience: Survival, Control, Reliability, Professionalism, Scale, Innovation, and Legacy. Firms may move up or down in response to shocks or changing circumstances. What makes the framework powerful is its discipline. At any given time, a company faces only one true constraint. Addressing it unlocks progress. Ignoring it creates fragility.

Resilience is the essential bridge between today’s stable cash flows and tomorrow’s growth.

Global capital markets remain abundant, with investors and acquirers seeking reliable returns. Two qualities consistently attract capital: stable cash flows today and credible plans to grow those cash flows tomorrow. Resilience is the bridge between the two.

Each level of the hierarchy lays the infrastructure to ensure that progress is not easily reversed. Liquidity cushions shocks. Reliability builds customer trust. Professionalism creates credibility in reporting and leadership. Scale turns growth into momentum. Innovation reduces dependency on a single core. Governance secures continuity across generations of leaders.

Empirical research supports this logic. Liquidity shortages are the leading cause of small business failure. Supply chain studies show that reliability, especially on-time delivery, is the customer’s most important expectation. Research on management practices confirms that professionalized governance and financial discipline drive productivity and higher valuations. And innovation research highlights the importance of optionality and bold bets in sustaining long-term value.

Each level of the hierarchy has a single constraint that must be resolved before moving forward.

1. Survival. Liquidity is the constraint. Metrics such as the quick ratio, payroll coverage, and line-of-credit utilization determine readiness to progress. Growth without cash is simply deferred failure.

2. Control. Visibility is the constraint. Firms must establish accurate job costing, reliable scheduling, and trustworthy inventory data. Without control, leaders are forced to manage by intuition.

3. Reliability. Customer trust is the constraint. On-time delivery, first-pass quality, and equipment uptime determine whether the company can be depended upon.

4. Professionalism. Management depth and accountability are the constraint. Product-line profitability, value-based pricing, and distributed leadership are prerequisites for institutional credibility.

5. Scale. Flywheel friction is the constraint. When repeat and referral revenue exceed half of sales and core processes remain stable, growth compounds rather than stalls.

6. Innovation. Optionality is the constraint. Resilience requires a portfolio of credible opportunities and the discipline to act boldly when the right one emerges.

7. Legacy. Governance is the constraint. Without independent oversight and succession planning, even well-diversified firms remain fragile.

Progress requires crossing each threshold in order; skipping levels leaves the business fragile.

The hierarchy functions as a diagnostic system, rooted in the Theory of Constraints, with free cash flow as the objective.

The Resilience Hierarchy differs from many frameworks in its diagnostic orientation. It does not prescribe universal best practices. Instead, it provides a logic for identifying where a firm is constrained and what must be addressed next. Every business is unique in its products, people, and markets. Yet the sequence of constraints is universal.

This design is consistent with the Theory of Constraints. At any point, one binding limitation governs the system’s performance. In the Resilience Hierarchy, that system is the business, and the performance measure is the ability to generate and grow future free cash flows. The hierarchy guides leaders to focus on the constraint most likely to limit those flows. Once that constraint is resolved, the next emerges, and the cycle continues.

For leadership teams, the practical benefit is clarity. Rather than diluting attention across many initiatives, they can concentrate resources on the one factor that will most increase resilience and cash-generating capacity. This sequencing reduces wasted effort, prevents premature expansion, and ensures that progress compounds rather than regresses.

Lower middle market firms benefit most from a disciplined focus on cash flow as the universal measure of resilience.

The framework is particularly relevant for firms in the lower middle market. These businesses are often too complex to rely on intuition yet too resource-constrained to absorb repeated shocks. Many are also family- or founder-led, which magnifies the importance of succession and governance at later stages.

For owner-operators, the hierarchy provides a roadmap that links daily decisions to the ultimate goal: higher free cash flow. Improving cash flow not only increases the money available to owners, but also lowers the cost of capital by strengthening lender and investor confidence. In turn, this raises enterprise value.

For investors, the hierarchy offers a lens for evaluating resilience and identifying where targeted interventions will create the most value. It frames every operational or strategic improvement in terms of its contribution to sustainable cash flows.

Resilience frees organizations from relying on grit by ensuring systems, not people, carry the weight of endurance.

The Resilience Hierarchy is both pragmatic and rigorous. By identifying and addressing the binding constraint at each stage, companies can move forward with confidence. They can withstand shocks, adapt to change, and compound free cash flows over time.

Crucially, resilience reduces the need for constant grit. Just as the Fram’s design spared its crew from the ordeal faced by Shackleton’s men, a well-constructed business spares its people from relying on endless stamina and improvisation. Grit may save a company in crisis, but resilience ensures it rarely needs saving at all. In an era defined by volatility, that design choice is the difference between surviving on courage and thriving on cash flow.