Insights on Value Capture and Growth Readiness

How industrial owners build resilience, attract capital, and capture the next layer of value before they sell.

The Continuity Capacity Test: A Solvency Index for Family Business Succession

Succession looks like a leadership decision until the founder steps out and hidden subsidies turn into real costs. The Continuity Capacity Test (CCT) shows whether cash flow can fund that handoff safely.

Move beyond succession planning: quantify the cash-flow capacity required to survive the founder’s exit.

TL;DR

A founder-led business can feel stable for years and still be structurally unready for continuity.

When the founder steps out, hidden subsidies become real costs.

Continuity creates a new annual load: successor livelihood, debt, and often the cost of replacing founder labor.

The Continuity Capacity Test (CCT) is a simple index: CCT = FCF ÷ Continuity Burden.

In family business succession, continuity is not a family problem. It is a solvency problem.

I. The moment of transition reveals the real economics

When Richard spoke about handing the business to his son, he described it as the natural next chapter. When David talked about the same moment later, he used a different phrase: “the whole weight of the place.”

They weren’t disagreeing. They were describing the same transition from opposite ends of a life.

Richard is 67. He built a plastics injection molding company that carried a family for four decades; three kids, steady schools, dependable Christmases, nothing extravagant, nothing insecure. His personal lifestyle sits around $140,000 a year. After a lifetime of disciplined saving he has put away about $1.2 million. To finish his retirement plan he needs liquidity from the business, so the company will borrow roughly $1 million to buy him out. That adds about $100,000 a year in new debt service.

On paper, the firm shows about $340,000 of seller’s discretionary earnings. That number looks like capacity. It is stable, repeatable, and in most operating contexts it signals a healthy small industrial company.

Yet that same number becomes something else the moment Richard retires. Not because the market shifts or the plant underperforms, but because the business has to start paying for what Richard has been quietly providing for free.

David is 32, married, with a two-year-old at home and another baby due soon. He earns about $180,000 in salary and benefits. It is a solid living, and it reflects a simple assumption: the company can support his household after the handoff, while also carrying the costs the handoff creates.

That assumption is where many transitions break. Continuity is not just a leadership change. It is a financial stress event that exposes what the founder was subsidizing.

II. The hidden subsidy problem in founder-led firms

Founder-led firms run on invisible subsidies. They are not deceptive; they are functional. They come from the same traits that keep owner-operators alive in competitive markets: frugality, endurance, and the habit of stepping in wherever the business is thin.

Over time those habits distort the firm’s true cost structure.

Two subsidies show up again and again in lower-middle-market industrial companies.

Unpriced founder labor.

Richard’s replacement value is estimated around $240,000 per year. That is what it would cost to hire an outside general manager, or to promote David into the top role and backfill David’s current responsibilities. While Richard is active, that cost is invisible. Once he exits, it becomes unavoidable, whether paid in cash or absorbed as successor overload.

Sweat substituting for capital.

Founders routinely solve problems personally instead of funding the systems that would solve them structurally. They manage key accounts themselves instead of building a commercial engine. They troubleshoot production instead of hiring technical leadership. They make capital decisions intuitively instead of formalizing policy. All of this is rational while the founder has energy. It becomes fragile once the founder steps away.

These subsidies create a comforting illusion: the business seems to have more slack than it truly does. Standard measures like SDE can overstate continuity capacity because they are calculated in a world where the founder is still inside the machine.

When the founder leaves, the enterprise is forced to operate at full economic cost for the first time in decades. That is why succession often feels like a cliff even when nothing “goes wrong.”

III. The continuity burden: what the successor firm must actually carry

When a founder exits an owner-led firm, four obligations rise to the surface. Together they make up the continuity burden, the annual load the business must support to survive the handoff.

Successor household income

A successor’s compensation is not a perk. It is the livelihood of a family that is often larger, younger, and costlier to sustain than the founder’s household was at the same stage.Replacement of founder labor

Whether explicit or implicit, the firm must replace the economic function of the founder. If no one is hired, the cost is paid in successor burnout and operational risk. If a leader is hired, the cost is paid in cash. Either way it is real.Existing debt service

Equipment-heavy industrial firms carry debt. That debt does not disappear during succession. It takes first claim on cash.New debt created by the buyout

Family transfers commonly require borrowing to pay out the founder. This converts ownership into retirement liquidity while keeping the business in the family. It also adds weight precisely when the founder’s subsidies disappear.

In Richard and David’s case, round numbers make the shift obvious.

What the business produces today:

About $340k in owner-adjusted benefit.

What the business must carry after the handoff (realistic case):

David’s household income: $180k

Replacement of Richard’s labor: $240k

Existing debt service: $200k

New buyout debt: $100k

Total continuity burden: about $720k per year.

Nothing dramatic changed. The market did not collapse. The plant did not fail. The only change was that Richard stepped out, and the business had to externalize what he used to subsidize.

Families often counter with the most optimistic alternative: the successor will absorb the founder’s duties; no one new will be hired.

Even that “lean” scenario fails economically.

Continuity burden without formal replacement labor:

David’s household income: $180k

Existing debt service: $200k

New buyout debt: $100k

Total: about $480k per year.

Against a firm producing $340k, the gap appears before a single dollar goes toward reinvestment, working capital, or maintenance CapEx. In practice, the successor is forced to choose between funding the household and funding the business. Either choice erodes continuity.

Replacement labor is not the swing factor. The swing factor is the mismatch between a business built to feed one household and a continuity model that demands two households plus debt and reinvestment.

IV. The Continuity Capacity Test (CCT): a simple lens for viability

The Continuity Capacity Test is a solvency index for succession.

CCT = FCFᵣ ÷ Continuity Burden

FCFᵣ is free cash flow after reinvestment. In plain terms, it is the cash the business truly has left after paying taxes and funding the baseline reinvestment required to stay healthy.

Continuity Burden is the annual load the business must carry once the founder exits. It includes successor compensation, existing debt service, buyout debt service, and any replacement-labor cost if the founder’s operational role must be filled.

If you have taken a loan recently, this logic will feel familiar. Your bank likely estimated your Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR). DSCR asks a simple question: “Does your cash flow cover your debt payments with a safety margin?”

The CCT is the same type of ratio, but aimed at the next stress event. It asks:

“Will your cash flow cover the future continuity load with a safety margin?”

That future load is broader than debt alone. It includes the successor’s livelihood and the cost of operating without the founder’s hidden subsidies. So where DSCR tests whether a business can survive a loan, CCT tests whether it can survive a handoff. Both are, at the core, capital allocation questions about future burden and risk.

In Richard and David’s case, the continuity burden ranges from roughly $480k in the optimistic scenario to roughly $720k in the realistic one. The business produces about $340k before reinvestment. The implied CCT index is too low either way. The result is not a judgment about intent or competence. It is a solvency signal.

The CCT separates two categories of firms:

Continuity-solvent firms: cash flow can support the handoff without degrading the business.

Continuity-deficient firms: healthy today, structurally unable to survive the founder’s absence.

Many firms fall into the second category without realizing it.

V. Owner translation: what the test means, depending on where you are

Continuity deficits are not rare in the lower middle market. They are structural.

A founder-led manufacturer can be reliable and profitable yet still fail continuity because the enterprise never needed to fund two households, replace top-level labor at market cost, and carry buyout debt at the same time. When that burden outruns resilience, continuity becomes fragile in ways the P&L does not predict.

What changes is not the family. What changes is the economic load.

If a company is early in its resilience journey

Survival, control, reliability, and professionalism are still being built. The priority is getting the core profitable and repeatable. Continuity planning at this stage is premature. Capacity has to come first. In practice, CCT will usually confirm that the firm is still working to be bankable, not yet ready to be buyable or buildable across generations.

If a company is in scale or innovation mode

The question becomes whether growth is being capitalized into surplus, or consumed as income. Continuity only works when the business produces more economic value than a single household can absorb.

If a company is approaching legacy

Continuity is the final stress test. It requires explicit capital discipline, formal replacement planning, and enough margin to fund two generations without starving the future. A continuity deficit becomes a valuation deficit the moment the next generation needs financing or an outside buyer prices the risk of the handoff.

The uncomfortable truth is also the liberating one: continuity does not fail because people want the wrong thing. It fails because the business is too small for the continuity you are asking it to support.

What to do next

If a generational handoff is on your horizon, run a Continuity Capacity Test. Use round numbers. Do not aim for precision on the first pass. Aim for honesty about the load your business will need to carry the day the founder steps away.

If the test passes, you can move on to governance and design.

If it fails, the work is not “succession planning.” The work is building capacity before you transfer responsibility.

Either way, you get clarity early enough to act, not react.

The Capital Window Is Closing: Why “Good Companies” Are Suddenly Stranded

Capital hasn’t vanished—it’s just become selective. After years of easy money, banks and private credit have shifted from rewarding growth to rewarding resilience. Owners who can show clear systems, disciplined decision-making, and measurable results will still raise, refinance, and grow. The next era belongs to companies that stay bankable, buyable, and buildable when the window narrows.

“Every credit index, we’re tightening across the board.” — Don McCree, Head of Commercial Banking, Citizens Financial Group, Q3 2025 Earnings Call

Across the lower middle market, capital hasn’t disappeared; it’s simply become selective. The Fed’s Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey shows that nearly half of U.S. banks tightened commercial lending standards for mid-sized borrowers through late 2024 and early 2025. GF Data reports deal volume down more than 30 percent from its 2021 peak. Private credit, despite managing more than $1.6 trillion globally, has narrowed its focus to sponsor-backed or governance-mature borrowers.

Capital still flows, but only to those who treat resilience as an operating system. In this cycle, allocators—not operators—define who stays bankable, buyable, and buildable.

Market Evidence: The Window Narrows

The tightening began in 2023 when rate policy and regulation started pulling in the same direction. After the collapses of Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic, new Basel III capital rules and tougher oversight pushed regional banks to hold more reserves against commercial loans. By early 2024, many lenders in the $10 to $100 billion asset range had scaled back new credit for owner-led companies.

At the same time, deposit costs surged. The average rate on interest-bearing deposits climbed from 0.06 percent in 2021 to more than 4 percent by mid-2024. That swing erased the margins regional banks once earned on low-cost liquidity. Most responded by stepping away from segments that demanded more monitoring and carried less collateral protection, with the lower middle market among the hardest hit.

Private credit stepped into the gap but cautiously. The sector now manages more than $1.6 trillion globally, up from $875 billion in 2020, according to Preqin. Yet underwriting has become stricter. Funds prefer sponsor-backed deals with strong reporting and governance. Independently owned firms often do not make it past screening.

Deal activity tells the same story. GF Data shows lower-middle-market volume down by roughly a third since 2021. Purchase multiples have fallen from about 7.5× to 6× EBITDA, and leverage has dropped nearly a full turn.

Liquidity hasn’t vanished. It has shifted toward companies that show discipline—those that act like stewards of capital, not just producers of it.

Owner Diagnosis: Why “Good” Companies Are Failing the Test

Many owners blame sentiment, but the change runs deeper. Credit and equity markets have moved from rewarding performance to rewarding resilience.

In 2021, profit was proof enough. With near-zero interest rates and abundant private capital, almost any solid balance sheet could attract financing. When the Federal Funds Rate rose from 0.25 percent to over 5 percent by mid-2023, borrowing costs multiplied and lenders began screening for durability instead of yield.

That is where many mid-market firms have hit a wall. They are efficient but hard to evaluate. Few have formal governance or automated reporting. Many cannot show how decisions get made or how cash is redeployed under pressure. The business works, but to outsiders it looks opaque.

This lack of visibility reads as risk. Lenders tighten covenants or walk away. Investors discount valuations or extend diligence. What owners experience as a liquidity problem is really a transparency problem, a re-pricing of trust.

Capital is still available. It is looking for companies that behave like investors in their own enterprise—the ones that make decisions with evidence, measure risk in real time, and can explain how they create value, not just that they do.

Allocator Solution: How Resilience Becomes Capital

The firms still raising capital or completing acquisitions have one thing in common: visible system maturity. Their lenders can trace how money moves through the business, from operations to reinvestment. They can see the logic, not just the results.

These companies treat resilience as a working asset. They build models that bend under pressure without breaking: recurring revenue, flexible cost structures, and governance that shortens the distance between signal and decision. When outsiders can see that discipline, they price the risk lower.

More owners are starting to operate this way, thinking like allocators rather than operators. The shift is practical, not theoretical. It comes down to three habits:

Measure resilience before you need it. Track liquidity, customer concentration, and reporting reliability as if a lender were already testing them.

Plan in short allocation cycles. Replace rigid annual budgets with ninety-day reviews that tie strategy directly to measurable deployment of time and capital.

Make the story match the structure. Ensure your stated strategy aligns with how the business actually spends and invests.

These are not new ideas. They have simply become the price of admission. The gap between “good company” and “credible borrower” now depends on the quality of evidence. Firms that institutionalize discipline earn cheaper debt, faster diligence, and stronger options when markets reopen.

In today’s market, maturity is not about size. It is about visibility. Operational strength alone is no longer enough. Resilience, made measurable, is what keeps a company bankable, buyable, and buildable.

Call to Action: The Discipline Dividend

Tight cycles separate effort from evidence. When money was cheap, almost any business could look like a safe bet. When the cost of capital rises, lenders and buyers look harder. What they are really searching for is proof that the company’s strength is not a story but a system.

This market is not hostile. It is honest. Owners who can show resilience—clear books, tested decisions, predictable cash—will still raise money and close deals. Those who build discipline into how they plan and invest will find that credibility travels further than optimism.

Now is the time to make your systems visible. Write down how capital gets deployed, how you adjust when pressure hits, how your team measures risk and reward. Build the habits before the next up-cycle so you can use them when it arrives.

The companies that do this will define the next phase. They will stay bankable when credit tightens, buyable when markets reopen, and buildable through every turn that follows.

The Owner as Investor: How to Write the Investment Thesis for Your Own Company

Owners can’t rely on instinct to grow across cycles. This article shows how to write the Investment Thesis for your own company—the disciplined capital plan that defines where to hold, reinvest, or acquire. Learn how investors build conviction, and how the same logic can help you compound value inside your business.

Turning resilience into a compounding system of value creation.

The Owner Who Started Thinking Like an Investor

Mark didn’t need to fix his business; he needed to decide what to do with it.

After twenty years running a CNC machining firm, Mark had built a company that was growing steadily and weathering industry swings better than most. He had already done the internal work most owners postpone. Quote cycles were cut in half, engineering setup times fell from two weeks to six days, throughput was up, margins followed, and cash flow was stable.

The company was strong but not yet compoundable. With capital building and operations humming, Mark faced a harder problem: how to grow without dilution or drift.

He wasn’t looking for an exit. He was looking for a system — a disciplined way to decide where each dollar of effort and investment would create the most durable return.

That search led him to write the investment case for his own company.

From Resilience to Discipline

In The Price of Resilience, we argued that resilience isn’t free; it’s priced. Buyers pay premiums for companies that can grow across cycles.

Growth across cycles doesn’t happen by instinct. It requires discipline in how capital is deployed: when to hold, when to reinvest, and when to acquire.

That discipline takes form in the Investment Thesis, the owner’s capital deployment plan built on the same logic investors use to decide whether a company can compound.

Investors never buy or hold without one. Owners rarely write one. The difference isn’t sophistication; it’s structure. Investors treat capital as a scarce resource to be allocated under uncertainty. Owners can, and should, do the same.

The Kernel and the Flywheel

Every company that compounds value over time does it through two interlocking mechanisms: the kernel and the flywheel.

The kernel is the company’s enduring differentiating expertise, the capability that creates disproportionate value and grows stronger each time it is applied. It is not abstract skill but disciplined execution, a method that turns precision into resilience and resilience into margin.

The flywheel is the repeatable system that applies that expertise across customers, products, or acquisitions so that every rotation reinforces the kernel and stabilizes cash flow.

If the kernel creates value, the flywheel creates scale.

Together they form the compounding engine of enterprise value: the kernel deepens capability; the flywheel multiplies its effect. Each turn makes the system stronger, more legible, and more resilient to shocks.

Mark’s Investment Thesis revolves around those two forces. The kernel is already defined. The next question is whether the flywheel can spin beyond his own walls.

Testing the Flywheel

The test comes in the form of a planned acquisition: a regional materials finisher serving the same aerospace customers. On paper it appears unremarkable—thin margins, uneven delivery, chronic rework. The kind of company that survives on tolerance, not advantage.

Mark sees something different. The weaknesses are structural, not existential. Their process lacks the control his firm has mastered. By installing his precision discipline—the kernel—he expects to create day-one accretion.

If the acquisition proceeds, his thesis projects measurable results within the first quarter: defect rates could drop by as much as 80 percent, throughput could rise 25 percent, and working capital should stabilize as process variation falls. The plan is to integrate tooling, inspection methods, and scheduling data to create one unified production system.

The kernel will create value. The flywheel will create scale.

Writing the Investment Thesis

Mark’s thesis guides the sequence, not the story. It organizes intuition into logic.

Define the Kernel. What differentiating expertise strengthens with use?

Design the Flywheel. How can that expertise be applied repeatedly to compound both capability and cash flow?

Allocate Capital. Invest only in initiatives that strengthen the kernel or accelerate the flywheel. Everything else is noise.

An Investment Thesis is not a vision statement. It is a proof statement. It defines how capital will behave inside the business—how each dollar converts risk into resilience and resilience into value.

Owners call this strategic planning. Investors call it underwriting—the work of proving where capital earns the best return. The language differs; the logic does not.

The Logic of Compounding

When investors underwrite a deal, they aren’t buying history; they’re buying predictability—the confidence that a system can perform across cycles.

An Investment Thesis allows an owner to do the same. It links operating performance to valuation outcomes, converting resilience into a measurable growth system.

Mark’s company no longer depends on intuition or momentum. Each improvement tightens the flywheel. Each cycle makes the next acquisition easier to model. The system becomes self-reinforcing: capital feeds capability, capability generates cash, and cash funds the next turn.

The Discipline of Holding and Reinvesting

Holding and reinvesting is not inertia. It is a capital decision with a forecastable return.

Mark could sell now and likely double the net proceeds from just a few years earlier. Holding and reinvesting, guided by a thesis that governs where each dollar goes, offers a higher risk-adjusted return than selling today.

That is the mental shift an Investment Thesis creates. The owner moves from reacting to valuation to constructing it.

From Operator to Underwriter

Writing an Investment Thesis marks a transition. The owner stops running a business and starts underwriting it.

That shift changes how decisions get made. Capital is no longer an act of hope but an act of logic. The company becomes its own proof of concept.

At BluGrowth, this is the work: helping owners formalize the logic that investors already use to price them, translating resilience into a compounding system of value creation.

Because markets don’t reward what you’ve built.

They reward what you can prove will keep building.

Download Mark’s Investment Thesis

See how BluGrowth structures the logic of value creation — and use the framework to start your own.

The Price of Resilience

When a deal falls apart, it’s rarely emotion—it’s math. This article explains how private equity reprices risk, why resilience commands a premium, and how the Investment Thesis turns predictability into value.

Markets don’t punish decline; they punish fragility

After the collapse of a pending sale of a mid-market precision manufacturer, both sides agreed on only one thing: the deal had died suddenly. The rest was interpretation.

Greg, the owner, still finds it hard to accept. “It was the same business,” he recalled in an interview. “One account doesn’t change who we are.”

Maya, a vice president on the investment team that withdrew its offer, remembers it differently. “The business didn’t change,” she said. “Our understanding of it did.”

Greg viewed the adjustment as a betrayal; Maya viewed it as calibration. David, the fund’s managing partner, later summarized their position: “We weren’t repricing the business. We were repricing the risk.”

In every deal, the price is the physical expression of the buyer’s Investment Thesis, the logic linking risk, time, and resilience into a forecast they can underwrite. A buyer’s model begins with expected returns and discounts future cash flows by the probability they will arrive as planned. Investors describe that adjustment through the language of discounted cash flow, or DCF. The “D” is the part that matters: discounting reflects the market’s confidence in future earnings. When resilience weakens, the discount deepens, and the model’s price follows.

In the lower-middle market, that distinction now defines valuation behavior. Buyers are not pricing growth so much as they are pricing durability. According to GF Data, companies with above-average financial characteristics—stronger margins, better systems, professionalized leadership—earned roughly 8 to 10 percent higher valuation multiples in 2024 than the market average. In practice, that difference translates to about half to one turn of EBITDA, a premium driven less by optimism than by confidence in resilience.

The math of fragility

A single lost customer changed nothing about the machines, the team, or the process. What changed was the company’s forecastability. The loss exposed dependency, revealing how thinly resilience was spread across revenue streams. In the model, that meant lower expected leverage, slower payback, and wider error bars. The valuation adjustment was not punishment; it was a recalibration of trust.

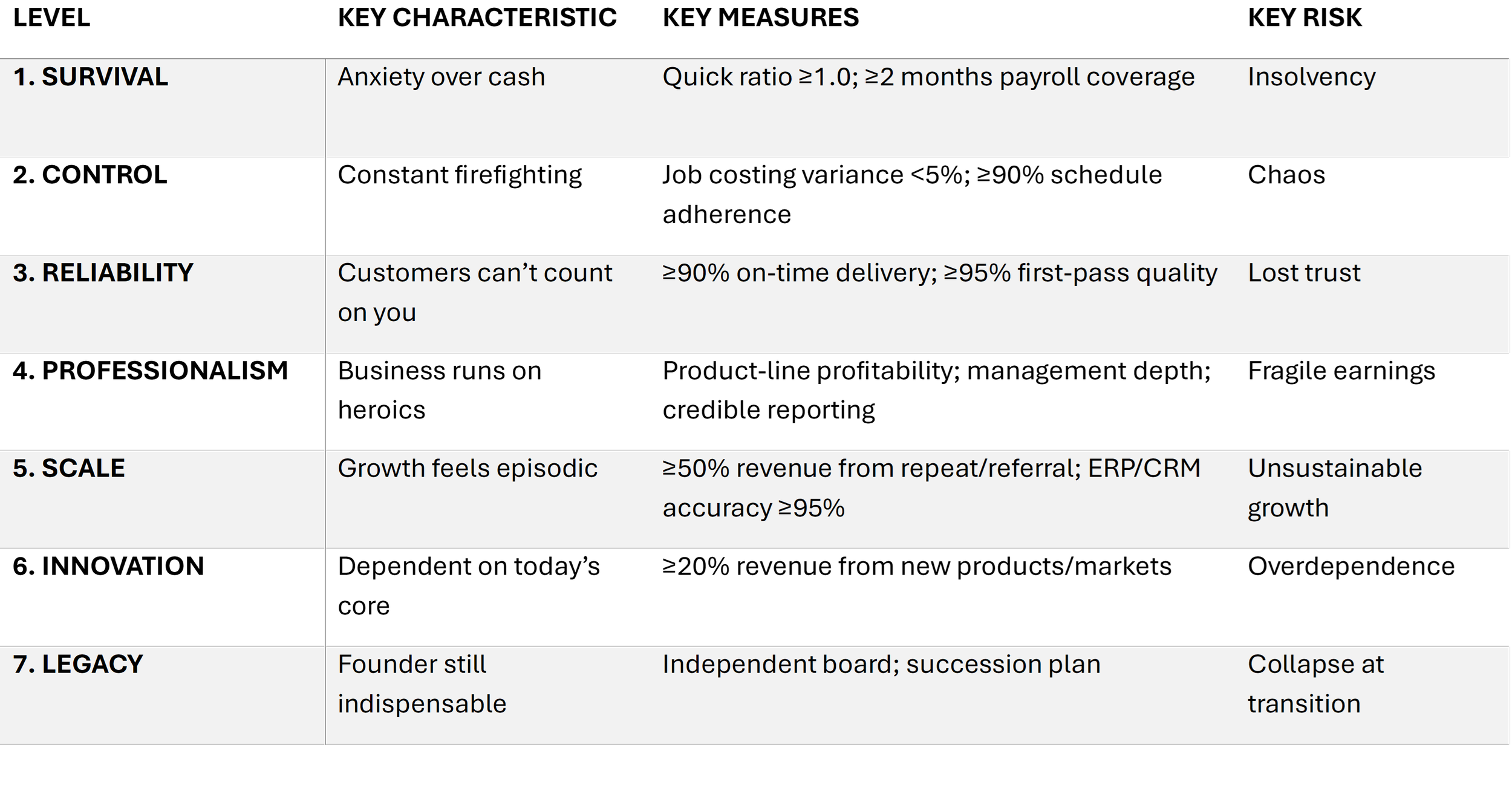

The BluGrowth Resilience Hierarchy™: seven levels of predictability

Resilience can sound abstract until it is structured. The BluGrowth Resilience Hierarchy™ defines that structure in seven levels, each building on the last:

Survive with Cash. Liquidity discipline; control your burn and working capital.

Control Operations. Establish process visibility and data cadence.

Deliver Reliably. Meet customer demand consistently, at predictable margins.

Professionalize the Numbers. Build accurate, timely reporting that supports decision-making.

Professionalize the Leadership. Broaden management capacity; reduce owner dependence.

Scale and Innovate. Allocate capital deliberately toward growth levers that fit the system’s maturity.

Build Legacy Value. Institutionalize culture and governance so the company endures beyond any one cycle.

Each ascent changes how outside capital perceives risk. A company at level two is fragile; cash-flow visibility is limited and execution depends on individual heroics. By level five, leadership and reporting routines have created stability that lenders can price. By level seven, resilience is systemic; the company behaves like a platform, not a project.

Greg’s business sat somewhere between level three and four. The loss of one major customer exposed the gap between Deliver Reliably and Professionalize the Numbers. The system worked, but it was not durable. That gap is what the multiple measured.

Inside the investor’s model

In diligence, EBITDA is the starting point, not the conclusion. The model layers in cash flow reliability, leverage capacity, and post-close workload. When visibility deteriorates, each of those assumptions shifts. The discount rate rises because execution risk feels higher. Lenders quote wider spreads. Operating partners see more unknowns to manage. What was a three-year stabilization plan becomes five. That inflation of uncertainty shows up as price.

Resilient businesses improve both halves of the valuation equation. The “D” in the DCF reflects confidence; the “CF” represents growth in future cash flows. Investments in systems, leadership, and transparency expand that future stream, turning resilience into yield. The more predictable the earnings, the clearer the compounding path, and the higher the price a model can justify.

Valuation practice confirms this pattern. GF Data reports that lower-middle-market buyouts with superior financial characteristics averaged about 7.8× EBITDA, compared with 7.2× for the full market in 2024—a direct, quantifiable reward for resilience.

Behind every multiple is a stack of assumptions about time, capital, and confidence. When an owner’s systems make those assumptions observable, the buyer’s required return drops, and the offer rises. The arithmetic looks like valuation, but what is being repriced is trust.

The anatomy of collapse

The hierarchy explains the logic of the downgrade. Greg had cash (level one) and control (level two) but lacked depth at levels four and five. There was no customer concentration dashboard, no second-line leadership ready to absorb disruption, no scenario analysis in the planning cadence. The business remained operationally sound but structurally brittle. When volatility arrived, it could not convert surprise into information.

In investor language, the deal lost its narrative coherence. The business no longer read as predictable, and in markets that discount uncertainty, that alone is enough to move price.

The investor’s imperative

Neither Maya nor David spoke with regret. They had a fiduciary responsibility to their limited partners to maintain portfolio predictability. A single fragile asset can distort fund performance. What looks like cruelty in a single deal is prudence at portfolio scale. The model did not reject the company; it rejected fragility.

Resilience is the multiple

Greg left the process certain he had been treated unfairly. From his perspective, the same business simply produced less profit. From theirs, the event revealed a structure they could no longer underwrite. Both were correct. The business did not break; its illusion of predictability did.

In selective markets, resilience is not safety; it is yield.

PE Is Not Buying EBITDA. It’s Buying Confidence.

Private equity doesn’t buy earnings—it buys confidence. When investors look at a company, they’re underwriting its ability to deliver future performance, not just its past EBITDA. This piece explores how “confidence gaps” in systems, leadership, and reporting quietly discount valuation—and what owners can do to close them before they sell.

Markets do not reward history; they discount uncertainty

“We don’t pay for last year’s EBITDA. We pay for the confidence we can grow next year’s.”

The remark, delivered without theatrics by a mid-market private equity partner, is inelegant but accurate. Multiples are not a reward for past excellence; they are a probability-weighted forecast of future execution. In lower mid-market SMB industrial deals, the real negotiation is not over price but over conviction.

This is why the same company can receive wildly different valuations from different buyers. The spread is not sentiment; it is risk discounting. PitchBook estimates that fewer than three percent of owner-led firms successfully complete a traditional sell-side process, while capital concentration continues to narrow toward funds with scale and confidence in post-close lift.

McKinsey’s study Beyond the Hockey Stick finds that roughly ten percent of firms capture more than eighty percent of total economic value creation over a decade. The distribution is not linear; it is a power law, and private capital prices accordingly. The pricing function is therefore a risk-adjusted forecast: is this company one of the ten percent that can compound, or one of the ninety percent that will merely endure? The buyers that are still deploying are selective, not generous.

Underwriting is the sorting mechanism.

Owners think they are being judged; the risk they absorb is being underwritten

The key misunderstanding among owners in industrial SMB manufacturing is that investors are pricing the business as it exists today. They are not. They are pricing how much of today’s EBITDA will still be standing once the owner leaves the room—and how quickly a buyer can compound it thereafter. A clean P&L does not answer that question. A QoE cannot answer it either. Only the operating system of the company can.

The underwriting sequence is blunt. First: “Is this company durable without the current owner?” Second: “Can we institutionalize what works without overpaying for the privilege?” Third: “Is the growth story credible inside the four walls, not just in the offering memorandum?” The multiple is not a judgment of worth but an output of underwriting: the present value of future net cash flows and terminal value. It is then discounted by the capital injections and execution risk required to achieve them.

Growth is not rewarded; legibility is

In one recent diligence discussion, the room stalled on the simplest of questions: “What business are we actually buying?” The owner had healthy EBITDA, a loyal customer base, and sensible unit economics. The problem was strategic drift. Five initiatives were being pursued at once, each potentially attractive, but none coherent. What looked like optionality to the operator appeared as drift to the buyer. The haircut was not punishment. It was uncertainty, priced.

Bain’s research on adjacency moves in industrial firms finds that more than 70 percent of unfocused expansions underperform their core, not because the markets are unattractive but because the operating system was never built to carry that variety.

This is the quiet truth of lower mid-market industrial underwriting: most valuation erosion is not caused by obvious weaknesses but by ambiguous intentions. Buyers can underwrite a bottleneck in a manufacturing or industrial SMB environment. They can underwrite a thin bench. They can even underwrite cyclicality if there is discipline in cash conversion. What they cannot underwrite is a company without a crisp answer to “why this model, at this scale, with this focus.”

Owner-reliance is therefore not the root concern; it is merely the most visible proxy for something larger: concentration of judgment. When all strategic direction lives in one head, the buyer assumes execution risk remains unpriced. The same dynamic applies to firms with sprawling initiative sets, product creep, or half-adjacent expansions justified only by “customers asked for it.” The fear is not mismanagement. The fear is diffusion.

For investors, confidence is not a feeling; it is infrastructure. It shows up in routinized decisions, reliable reporting cadence, constraint-aware capital allocation, and a recognizably bounded strategy. Growth, in that context, is not a hope but a process, and what many owners call exit readiness is simply the point at which the operating system becomes legible to a buyer. The more predictable the process, the narrower the haircut.

This is why the best offers do not reward scale so much as clarity. A smaller firm with a defensible core and visible path to systematized expansion will often outprice a larger firm with a blurred identity. Size without focus is not resilience. It is leverage without a thesis.

The market’s selectivity is frequently misread as stinginess. It is better understood as underwriting discipline. When capital is choosy, ambiguity is expensive. What is being purchased is not the last twelve months of performance but the institutional momentum of the next thirty-six.

In the end, what is being priced is legibility.

A company easy to read is a company easy to scale.

Originally published on LinkedIn. Updated and republished here with additional insights.

The Silver Tsunami Meets a Capital Squeeze

A wave of owner transitions collides with tightening capital markets. This piece explores how unsolicited offers, interest rates, and capital access are forcing business owners to decide: sell now or build value first?

How owners in their 60s can decide, without romance or panic, whether to sell now or invest and sell later.

Anne (not her real name, to protect her employees) faces a familiar choice. She is 63, runs a tidy fabrication shop that does CNC machining and precision lathing, employs 14 people, and earns about $2 million in EBITDA. Private equity buyers have called many times. The choice appears simple: take the check and exhale, or keep operating and revisit a sale in a few years. There is no formal succession plan, and reporting still revolves around the owner. Anne’s aim is ordinary and admirable: do what is best for her family, her employees, and her customers.

The backdrop argues for discipline rather than drama. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, more than half of business owners are 55 or older, which means a lot of succession decisions are coming. At the same time, PitchBook and McKinsey describe a K-shaped private equity climate, where the largest funds continue to attract an outsized share of commitments while smaller deals face choosier capital. Translation: larger, more professionally-run companies are seeing attractive deals while smaller, owner-operated businesses are seeing fewer and riskier deals.

So how does an owner decide? Treat it as a capital allocation problem. Put two paths on the same footing:

Sell-now path: after-tax cash at close, plus the expected value of any rollover. (Earn-outs may be off-limits if the deal relies on SBA debt.)

Invest-then-sell path: after-tax exit proceeds on higher EBITDA and, if earned, a better multiple, minus owner out-of-pocket capex after tax shields and realistic financing, plus the present value of operating cash while you hold the business. Then probability-weight the plan and apply an owner-specific risk haircut.

That last term, cash while you wait, is often ignored. It should not be. On a $2 million EBITDA base with sensible cash conversion, it is not pocket change.

Policy also matters. The current toolkit leans toward investing in manufacturing at home, even if trade policy keeps everyone on their toes.

Advantages that favor staying and strengthening

Accelerated expensing for equipment. The latest tax rules restore 100% bonus depreciation for qualifying property. There is also a new elective 100% allowance for certain production assets. In plain English, a CNC lathe or automation cell with a real payback can be expensed up front, which improves after-tax returns and shortens breakeven. Policymakers are using the tax code to encourage domestic production, and owners can use that nudge to fund practical upgrades.

SBA programs with higher-impact options. Standard 7(a) and 504 loans remain the backbone for smaller companies, and the new MARC revolving-credit channel is designed to broaden working capital for manufacturers. None of this replaces bankability, but it can lower the owner’s cash flow risk and smooth the path when paired with modest leverage and credible paybacks.

Repatriation intent, practical effect. Taken together, full expensing and manufacturer-focused credit are a signal. Washington wants more production at home, and it is trying to make domestic capex cheaper and financing more available.

The offset: tariff and policy uncertainty

Tariffs and related documentation rules have moved more than once in recent years. Metal-heavy shops felt that quickly in landed costs and lead times of raw materials. The practical response is not fatalism, it is resilience planning. Assume more noise in input prices and delivery schedules, and stress-test your plan for cash flow risks with professional treasury management.

What actually improves outcomes on the 'stay' path

Resilience in structure. Reduce key-person dependence, diversify top-customer exposure, and update a simple monthly reporting pack that includes a P&L, a cash bridge, a trailing twelve month view, orders, backlog, on-time delivery, and scrap or rework. Add one capable manager under the owner. Buyers pay for Resilience, not personality.

Resilience in earnings. Invest where cash conversion improves. For a shop like Anne’s, that usually means quick-change tooling, program standardization, removing the bottleneck cell, and tightening pricing and procurement. Vanity capex is banned. Every material dollar should show up in unit economics or in demonstrable, sellable capacity.

Resilience in financing. Use accelerated expensing and appropriate SBA, USDA, or conventional mixes to lower the equity check without over-gearing. Share a detailed business plan with your lender that covers use of funds, paybacks, KPIs, and the monthly reporting pack. Treat the first quarter as a proof-of-execution window.

There remain honest reasons to sell now. If the odds of executing a short list of improvements are low, for example a thin bench, concentrated revenue, or volatile demand, or if personal constraints loom, for example health, energy, or appetite for another cycle, certainty is valuable. A sale with rollover can be a pragmatic middle path, but remember that you are underwriting someone else’s execution and timeline.

Back to Anne. We ran her numbers two ways. Sell now, and she likely nets about $5 million after tax. That estimate assumes typical lower-middle-market multiples for owner-dependent shops and a blended capital-gains rate that varies by state. Invest, then sell, and the picture shifts. One senior hire, two process upgrades with measured paybacks, a modest tuck-in to smooth customer concentration, and disciplined pricing could plausibly lift EBITDA by a quarter to a third over four years. With accelerated expensing on qualifying capex and steady operating cash along the way, our estimate for a four-year exit is nearly $10 million after tax, nearly doubling the economic value created for Anne. These are estimates, not promises. Execution and cycles matter.

Three rules keep the exercise honest:

Stress-test conservative, base, and ambitious cases. If it only works in ambitious, it does not work.

Bring in the banker early, not late. Show paybacks and the monthly pack.

Plan at the household level. Liquidity timing, taxes, estate planning, and portfolio risk need to fit together. A qualified wealth advisor should sit at the table before numbers harden.

Where does that leave owners? In a selective market, Resilience is the product. The decision is not whether to retire or grind, it is whether value can be created, reliably, before you sell. If yes, build Resilience and harvest cash. If not, price for certainty and move on.

Originally published on LinkedIn. Updated and republished here with additional insights.

When Growth Demands Its Price

Every company pays for growth—either in cash, capacity, or control. This article breaks down how growth amplifies weaknesses and what it takes to build systems that scale without cracking.

Growth is Faustian. It tempts firms with promises of wealth and power while concealing the risks that can undo them. Built on strength, it compounds resilience into cash, credibility and value. Built on weakness, it accelerates fragility into cash strain, chaos and mistrust.

Every owner wants growth. Bankers cheer it. Economists measure it. Yet growth is not salvation. It is an amplifier. It multiplies what already lies inside a business, exposing cracks as quickly as it rewards discipline. The question is not whether to grow, but whether the business can withstand what growth will amplify.

Growth pains

When liquidity is thin, growth tightens the squeeze. More orders mean more receivables, more inventory and less cash. This is overtrading: expanding faster than working capital can bear.

When discipline is weak, growth magnifies the chaos. “A few late shipments today are not going to improve if we double the volume,” warns Bill W., a warehouse manager. At ten million dollars in revenue, delays are irritants. At fifteen million, they are reputational damage. Reliability does not scale by itself.

When credibility is missing, growth breeds mistrust. “We are asked for larger facilities, but the cash flows can’t support it,” says a commercial banker. Customers share the concern, hesitating to place bigger orders with suppliers who fumble the basics. Hustle may carry a firm through its early years. But it does not scale. Without resilience—systems, discipline and focus—growth turns hustle into a liability.

Strength training

If liquidity is secure, growth generates cash. Fixed costs spread wider, operating leverage takes hold and incremental sales deliver more profit.

If reliability is high, growth deepens trust. Orders arrive on time. Quality is consistent. Reputation compounds. One satisfied customer becomes a stream of repeat and referral business.

Professional management builds credible growth. Transparent reporting and deeper teams reduce risk. “Once the numbers were clear and the team was deeper, we were comfortable lending more at better terms,” notes another banker. Growth not only expands earnings, it lowers the cost of capital and lifts valuations.

Fault lines under pressure

The Resilience Hierarchy, modelled on Maslow’s pyramid, sets out the sequence. At the base the constraint is liquidity. Then come control, reliability, professionalism, scale, innovation and, at the summit, legacy. Growth will amplify whichever constraint is unresolved. Liquidity gaps become cash crises. Weak governance becomes founder dependence. But once the constraint is solved, growth amplifies strength instead.

This is not a tale of good growth and bad growth. Growth is always growth. Its effect depends on the foundations beneath it.

Proof in the margins

Take a ten-million-dollar contract manufacturer. At first, more orders meant more late deliveries, more angry customers and less clarity on profitability. Expansion multiplied weakness. The firm then fixed reliability and professionalism. On-time delivery rose above ninety percent. Product-line profitability became clear.

When growth returned, it multiplied strength instead. Margins improved. Cash flow doubled. Bankers offered cheaper credit. “It finally felt like the business was working for us, not the other way around,” recalls the owner. Within four years EBITDA rose from one million to 2.3 million. Enterprise value climbed from 5.5 million to 13.8 million. Growth became a reward for resilience rather than a punishment for fragility.

Take one down, pass it around

The BluGrowth formula is simple: find the constraint, remove the constraint, repeat. Each time a bottleneck falls, another appears. Take one down, pass it around. Progress is steady, compounding, and focused. This rhythm turns growth from a source of anxiety into a source of wealth.

Growth is not a strategy. It is a force multiplier. Owners must ask what weaknesses growth will expose. Bankers must ask what strengths it will magnify. Investors must ask whether the returns justify the risks that growth will amplify.

The Resilience Hierarchy: A Framework for Enduring Growth

The Resilience Hierarchy outlines five levels of business maturity—from liquidity to legacy—that predict whether growth endures or collapses.

Resilience is not grit; it is the deliberate design of systems that prevent reliance on heroics.

Resilience has become one of the most valuable yet elusive qualities in business. It is often confused with grit. Grit asks individuals to persevere through adversity by sheer willpower. Resilience, in contrast, is about designing systems so that endurance is not left to human stamina alone.

The distinction is visible in polar history. The crew of the Endurance, led by Ernest Shackleton, survived only by extraordinary grit after their ship was crushed by ice. By comparison, Fridtjof Nansen’s Fram was designed with a rounded hull that allowed it to ride above the pack ice rather than be destroyed by it. The crew still faced hardship, but they did not need superhuman endurance simply to survive. The difference was not in courage but in design.

Businesses face the same choice. They can rely on grit—leaders and employees working harder, longer, and under increasing strain—or they can build resilience into the enterprise itself. The Resilience Hierarchy offers a framework for doing the latter.

The model adapts the logic of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to the realities of business growth. But unlike Maslow’s psychology, which aims for self-actualization, the Resilience Hierarchy is built as a constraint system, with future free cash flow as the objective function. Every for-profit enterprise has the same ultimate goal: to increase free cash flow. This delivers money to owners, lowers the cost of capital, and raises enterprise value. The hierarchy exists to help leaders identify and address the constraint most likely to limit those flows.

The hierarchy identifies seven levels of resilience: Survival, Control, Reliability, Professionalism, Scale, Innovation, and Legacy. Firms may move up or down in response to shocks or changing circumstances. What makes the framework powerful is its discipline. At any given time, a company faces only one true constraint. Addressing it unlocks progress. Ignoring it creates fragility.

Resilience is the essential bridge between today’s stable cash flows and tomorrow’s growth.

Global capital markets remain abundant, with investors and acquirers seeking reliable returns. Two qualities consistently attract capital: stable cash flows today and credible plans to grow those cash flows tomorrow. Resilience is the bridge between the two.

Each level of the hierarchy lays the infrastructure to ensure that progress is not easily reversed. Liquidity cushions shocks. Reliability builds customer trust. Professionalism creates credibility in reporting and leadership. Scale turns growth into momentum. Innovation reduces dependency on a single core. Governance secures continuity across generations of leaders.

Empirical research supports this logic. Liquidity shortages are the leading cause of small business failure. Supply chain studies show that reliability, especially on-time delivery, is the customer’s most important expectation. Research on management practices confirms that professionalized governance and financial discipline drive productivity and higher valuations. And innovation research highlights the importance of optionality and bold bets in sustaining long-term value.

Each level of the hierarchy has a single constraint that must be resolved before moving forward.

1. Survival. Liquidity is the constraint. Metrics such as the quick ratio, payroll coverage, and line-of-credit utilization determine readiness to progress. Growth without cash is simply deferred failure.

2. Control. Visibility is the constraint. Firms must establish accurate job costing, reliable scheduling, and trustworthy inventory data. Without control, leaders are forced to manage by intuition.

3. Reliability. Customer trust is the constraint. On-time delivery, first-pass quality, and equipment uptime determine whether the company can be depended upon.

4. Professionalism. Management depth and accountability are the constraint. Product-line profitability, value-based pricing, and distributed leadership are prerequisites for institutional credibility.

5. Scale. Flywheel friction is the constraint. When repeat and referral revenue exceed half of sales and core processes remain stable, growth compounds rather than stalls.

6. Innovation. Optionality is the constraint. Resilience requires a portfolio of credible opportunities and the discipline to act boldly when the right one emerges.

7. Legacy. Governance is the constraint. Without independent oversight and succession planning, even well-diversified firms remain fragile.

Progress requires crossing each threshold in order; skipping levels leaves the business fragile.

The hierarchy functions as a diagnostic system, rooted in the Theory of Constraints, with free cash flow as the objective.

The Resilience Hierarchy differs from many frameworks in its diagnostic orientation. It does not prescribe universal best practices. Instead, it provides a logic for identifying where a firm is constrained and what must be addressed next. Every business is unique in its products, people, and markets. Yet the sequence of constraints is universal.

This design is consistent with the Theory of Constraints. At any point, one binding limitation governs the system’s performance. In the Resilience Hierarchy, that system is the business, and the performance measure is the ability to generate and grow future free cash flows. The hierarchy guides leaders to focus on the constraint most likely to limit those flows. Once that constraint is resolved, the next emerges, and the cycle continues.

For leadership teams, the practical benefit is clarity. Rather than diluting attention across many initiatives, they can concentrate resources on the one factor that will most increase resilience and cash-generating capacity. This sequencing reduces wasted effort, prevents premature expansion, and ensures that progress compounds rather than regresses.

Lower middle market firms benefit most from a disciplined focus on cash flow as the universal measure of resilience.

The framework is particularly relevant for firms in the lower middle market. These businesses are often too complex to rely on intuition yet too resource-constrained to absorb repeated shocks. Many are also family- or founder-led, which magnifies the importance of succession and governance at later stages.

For owner-operators, the hierarchy provides a roadmap that links daily decisions to the ultimate goal: higher free cash flow. Improving cash flow not only increases the money available to owners, but also lowers the cost of capital by strengthening lender and investor confidence. In turn, this raises enterprise value.

For investors, the hierarchy offers a lens for evaluating resilience and identifying where targeted interventions will create the most value. It frames every operational or strategic improvement in terms of its contribution to sustainable cash flows.

Resilience frees organizations from relying on grit by ensuring systems, not people, carry the weight of endurance.

The Resilience Hierarchy is both pragmatic and rigorous. By identifying and addressing the binding constraint at each stage, companies can move forward with confidence. They can withstand shocks, adapt to change, and compound free cash flows over time.

Crucially, resilience reduces the need for constant grit. Just as the Fram’s design spared its crew from the ordeal faced by Shackleton’s men, a well-constructed business spares its people from relying on endless stamina and improvisation. Grit may save a company in crisis, but resilience ensures it rarely needs saving at all. In an era defined by volatility, that design choice is the difference between surviving on courage and thriving on cash flow.

Five People You Need Before You Need Them

Growth and exit readiness require a trusted advisory circle. These are the five professionals every owner needs in place before scaling or selling.

Running a business in the lower middle market ($2.5M – $50M) is not a solo drive. It is more like NASCAR.

The driver is the star of the show, carrying the weight of the race with skill, endurance, and split-second decisions. They manage the heat, the stress, and the reflexes for hours at a time. The best drivers also know they cannot win alone, which is why they surround themselves with the best pit crews.

Business works the same way. Opportunities come fast. Crises do not send a warning flag. You cannot afford to scramble for help at the last minute. You need your pit crew ready, practiced, and trusted long before the pressure hits.

That is why these five advisors matter most. They are not just specialists. They are your pit crew, coordinated, fast, and trusted enough to keep your business in the race and ahead of the pack.

1. The Wealth & Estate Advisor (The Crew Strategist)

In NASCAR, there is always someone thinking about the long game, when to pit, how to save fuel, and how to finish strong. The wealth advisor plays that role. They ensure that business success turns into lasting family wealth, not just paper wins. They bring in estate attorneys and trust experts to protect what you have built, making sure the endgame is not lost in the rush of the race.

2. The Lawyer (The Master Mechanic)

Your lawyer is the one making sure the machine can handle the track. Contracts, compliance, and disputes are like the nuts and bolts holding the car together. One loose piece can cost you the whole race. A trusted lawyer not only protects you but knows when to bring in specialty mechanics like IP, employment law, or litigation to keep you running clean.

3. The Banker (The Fuel Chief)

Without fuel, you are not racing. The banker is your fuel chief, making sure you always have access to the capital needed to compete. The right banker does not just top off the tank. They bring options: acquisition financing, treasury services, SBA loans, and private investors. They understand your ratios, your limits, and your goals, and they know how to keep you running at peak speed.

4. The CPA / Financial Advisor (The Spotter with the Data)

Every NASCAR driver relies on the spotter, the person with the data, angles, and foresight they do not have in the car. That is your CPA. They keep the numbers clear and forward-looking, flagging risks before they cause a wreck. From proactive tax planning to cash flow strategy, to fast-track Quality of Earnings when a deal comes up, the CPA is your set of eyes above the track.

5. The Value Creation Advisor (The Crew Chief)

Every pit crew needs a leader who calls the sequence, synchronizes the team, and manages the race strategy. That is the Value Creation Advisor. They integrate legal, financial, and operational input into one plan, making sure all the other advisors are working in sync. Their job is to keep you focused on the big picture, building enterprise value lap after lap.

Trust Takes Time

A NASCAR pit crew does not magically deliver under pressure. They train together, build trust, and refine their timing long before race day.

Advisors work the same way. You cannot expect them to deliver seamlessly if you only call them in at the last minute. Trust is two-way. They need to know your business and your goals just as much as you need to know their capabilities. And that takes time.

Who is Your Go-to Crew?

A Charlotte-based owner in the industrial services space got the call: a chance to acquire a competitor in an off-market bolt-on deal. The opportunity was rare, but the window was short.

The first call went to the Value Creation Advisor, who already knew the five-year plan and the bigger strategy. Immediately, they started working through the big questions: How does this acquisition fit into the enterprise? How does it change the five-year plan? What is the impact on the ecosystem? Where are the synergies? What is the net economic value?

While the VCA worked strategy, the Banker got to work on financing. Knowing the leverage position and debt service hurdles, the banker pulled in options, SBA and conventional lenders, commercial real estate specialists, and private investors, to map out the best fit.

The CPA jumped in on the numbers, building a Quality of Earnings report in days. They set up the secure data room, validated the financials, and flagged critical contracts for the Lawyer.

The Lawyer moved quickly, reviewing key agreements and drafting documents to protect the owner from liabilities.

Meanwhile, the Wealth Advisor stress-tested the deal structure to ensure the owner’s long-term family goals were not compromised.

Because of the high degree of trust across this pit crew, and their extended networks, the deal was agreed in days and closed in weeks. A timeline that usually takes months.

The difference was not luck. It was trust, built over years, that delivered when it mattered most.

How to Build Your Pit Crew

Having a name is not enough. To turn a list of advisors into a trusted team, you need to invest in the relationships, figuratively and literally.

Start with your network. If someone you trust trusts them, that is a good sign they will be the right fit. A referral carries more weight than a cold introduction.

Once they are on your radar, put in the time:

Engage them regularly. Call your advisors to talk about your business, even outside of specific transactions. The more they know your context, the faster they will perform when it matters.

Invest consistently. Your wealth advisor should already be actively managing part of your personal picture. Your lawyer and CPA often work best on retainers, that way they are in your corner before you pick up the phone.

Schedule check-ups. At minimum, a Value Creation Advisor should sit down with you annually to review your five-year plan, stress-test assumptions, and recalibrate strategy.

Like a NASCAR crew, performance under pressure only comes from reps, trust, and preparation. You cannot bolt a team together on race day.

The takeaway: These five advisors are your pit crew. Build the relationships early. Develop trust before the caution flag flies. So when the race is on the line, you are not scrambling for help, you are pulling into pit lane and your team already knows exactly what to do.